How Do School Uniforms Shape Sexuality?

Schools, which form an integral part of a student’s formative years, cater to individuals coming from different socio-economic identities and backgrounds. It acts as a space where primary socialization takes place, where students are taught “how” to become a part of the structure; of the society. However, this process is highly gendered and heteronormative in nature. The culture in schools acts according to the dominant norms, it teaches students social rules which are in accordance with the already existing structure in the society. One of these practices include enforcing stringent uniforms and dress codes so as to maintain discipline and order.

In this article, we seek to see the implications of school uniforms in young adults and how it controls and shapes sexuality in schools. This discourse primarily focuses on the implications of implanting school uniforms in young adults and the repercussion of the former in exercising sexuality. Patriarchy, the eons old institutions that bind us in gender roles, shackling us from exercising beyond the predetermined marks of our space. School dress codes navigate through the narrow spaces to establish a power dynamic in young minds. Oftentimes, this restraint takes a bigger shape in molding young bodies and ripping it off its agency of allowing and exploring various areas of sexuality. In this, we take a deep dive and unwind some of the factors.

“Good Girls are Asexual”

Academic performance is given the topmost priority in school. Issues about sex and sexuality, especially for adolescent students, are neglected and ignored. As Piyali Sur notes, “Schools discipline students’ bodies to prohibit any spilling over of sexuality that may “pollute” the educational environment. This notion links bodies of young girls to morality, linking it to the idea of purity. This creates the image of a “good” girl, one who is seen to be devoid of any passion and desire, has to be sexually unknowing, and in no way signals sexual availability.” Sur writes, “Adolescent girls are constantly reminded not to dress provocatively, keep themselves away from strangers, and not to venture outside protected zones. In this way, schools operate as a space of regulations, hierarchical divisions and homogenisation. This view of desexualising young students disempowers them from becoming sexually responsible citizens. It sees students as “non-sexual” or “asexual” thus stripping them of their agency.”

Along with viewing students as non-sexual, schools also speak of gender essentially through a heterosexual point of view, thus also shaping masculinity and femininity from a heteronormative standpoint. Heterosexuality is the invisible term when sexualities are spoken of. Heterosexuality is reinforced physically through uniforms. The strict divisions of what a “girl” and what a “boy” should wear, regulates and reproduces gender and heterosexual divisions. These divisions are then upheld by practices of ridiculing men who are “effeminate” and vice versa. Feminine behavior is also compared to gay behavior and “feminine” labels are constantly used in a derogatory manner for those who come from marginalized gender identities and sexual orientations. This not only leads to “othering” and “marginalization” but also reproduces dominant structures of hegemonic masculinity.

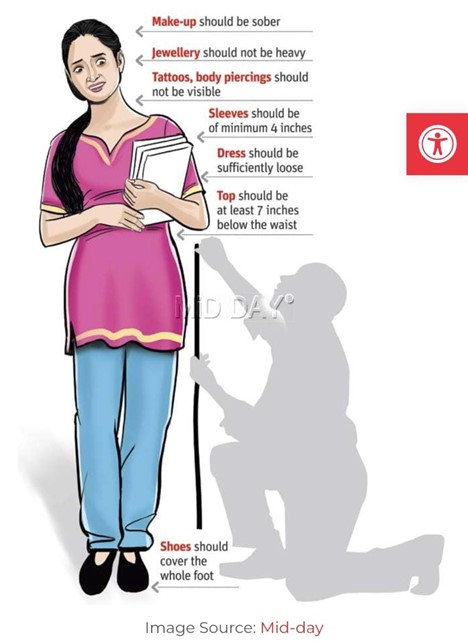

This constant policing is done because bodies matter at school. Dress codes and uniforms shape students to submit to the authority of educational institutions. Different regulations like skirts below knee length, physical distancing between binary genders, “no tight fitting” shirts, no jewelry or makeup is all essentially done to render bodies docile and to domesticate unruly bodies.

PATRIARCHY: ROOT OF IT ALL

While we discuss the various restraints on young bodies’ exercising their sexuality, patriarchy has a larger role to play. When we assign certain ‘standards’ or ‘norms’ to an already existing divide we create an even more distinct bifurcation in how one must behave and what is expected out of them. On many occasions we have come across the rule of wearing braids, the skirt length should be below the knee, no heavy jewelry, no makeup, no flashy ornaments. In any instance, if a girl is seen provoking against the said rule, they are ‘allowing’/ ‘inviting’ male gaze. They are, in short, ‘asking for it’. Remodeling our desires to dress up as who we are and tending to be ‘modest’ to the male gaze perpetrates rape culture in ways that is blind to the eyes. It allows men to believe women are coveted, sheltered and easily oppressed. The power dynamic that already exists between an institution vs an individual grows in size and spreads to the larger masses as teachings and norms to be followed. These minuscule checkings decided what was ‘right’/’moral’ completely disregarding the important factor of growing bodies and the changes one goes through. I remember, in a very vague memory, one of my school teachers once pointed out why was I not wearing a white or nude bra and why my bra was coloured? The authority to step over the boundary to my personal space alerted me severely and therefore also created caution in my mind for my growing body.

Consistently, putting the onus of dressing ‘modest’ on girls puts them in light of objectification, sexualisation. Dress codes primarily function as a restraint on exercising agency and autonomy on one’s own individualistic choices rather than questioning the evils in existence. It is where, ‘she was asking for it’ mindset starts breeding and grows so large, it’s untameable.

CONCLUSION

Michelle Fine argues that the anti-sex rhetoric surrounding sex education and school-based health clinics does little to enhance the development of sexual responsibility and subjectivity in adolescents. A significant absence of missing discourse on sexual health related topics in schools and educational institutions constantly subjects adolescents to unsolicited resources to acquire knowledge. In doing so, they absolve themselves of any qualitative understanding of their body, sexual rights and sex in general. They imbibe a warped version of sexual education which again allows the perpetration of rape culture.

Radical feminist lawyer Catherine MacKinnon (1983), views heterosexuality as essentially violent and coercive. In its full conservative form, proponents call for the elimination of sex education and clinics and urge complete reliance on the family to dictate appropriate values, morals, and behaviors.

Ideally, the predisposition of dress codes is to hold back on women and their ability to think and ask questions about their bodies. It strips young adolescents from actualizing their lived experiences. To navigate new feelings. The adolescent female rarely reflects simply on sexuality. Her sense of sexuality is informed by peers, culture, religion, violence, history, passion, authority, rebellion, body, past and future, and gender and racial relations of power (Espin, 1984; Omolade, 1983). For a young woman, being repeatedly policed for her clothes, behavior, choices is a terrible thing to be experiencing. It alters their brain chemistry, that is exactly where insecurity starts spawning, they grow like molds and serious psychological repercussions take place. It is essential for people, especially women, to have a space to exercise their rights and agency in exploring their bodies. It’s important to have conversations about female pleasure, female bodies and choices. History has shuttered away any semblance of understanding of our bodies. To iterate, we know very little, which is why it is easier to feed the wrong to the masses.

When we strip adolescents of their agency, of their choice to make decisions for their own bodies, we are also denying them their right to healthy, safe and accessible resources about their sexual health and reproductive rights. When we see bodies just from the lens of stigma, we neglect the pleasure and the desires which our bodies deserve. To give more importance to bodies and to acknowledge adolescents as sexual beings is to give them the power to own their bodies and to move towards a more inclusive space where sexual and reproductive health rights matters.

Written by: Debapriya and Shatarupa

Author